The Art Form

The Tinwood Foundation’s core art holdings consist of works made by Black Americans living in the Southern United States during the mid-to-late twentieth century and early twenty-first century, a period coinciding with the civil rights movement and the decades of social change that followed. During those years, a long-germinating art form came into bloom. These artists have pursued their individual creative visions while nurtured by, and immersed in, a vibrant culture already well-known for its influential achievements in other art forms, music especially. The artists have also felt called to open their private aesthetic practices towards public display and discourse. While bearing witness to the complex realities of their lives and times, they have imagined alternate possible futures for themselves and the wider world.

The artists’ biographies encompass the sweep of twentieth-century America, from the largely rural, agricultural Jim Crow South, with its doctrine of segregation, to the social and technological transformations of the post–World War II era. The second half of that century, and the first decades of our current one, have seen the emergence of the civil rights movement and urbanization, as well as upheavals to (and growth of) the Southern economy. The artists’ stories and perceptions emanate a hard-won authority traceable to their participation in the overlapping histories of multiple eras, refracted through art’s varied ambitions to inspire, to unite, to rethink, and to pose questions.

It is nevertheless difficult to generalize about the artists’ backgrounds. Many have had limited formal training and little-to-no art-specific education—with the notable exception of quilters, who typically receive training from networks of elders as a part of their upbringing. Yet, as primarily self-taught creators, they have acquired their artistic knowledge and proficiencies in numerous and varied ways. Many have specialized skills developed through their occupations and trades. And many have favored seemingly nonartistic materials, particularly cast-off, recycled, and found objects and goods—often freely mixed with fine-art media.

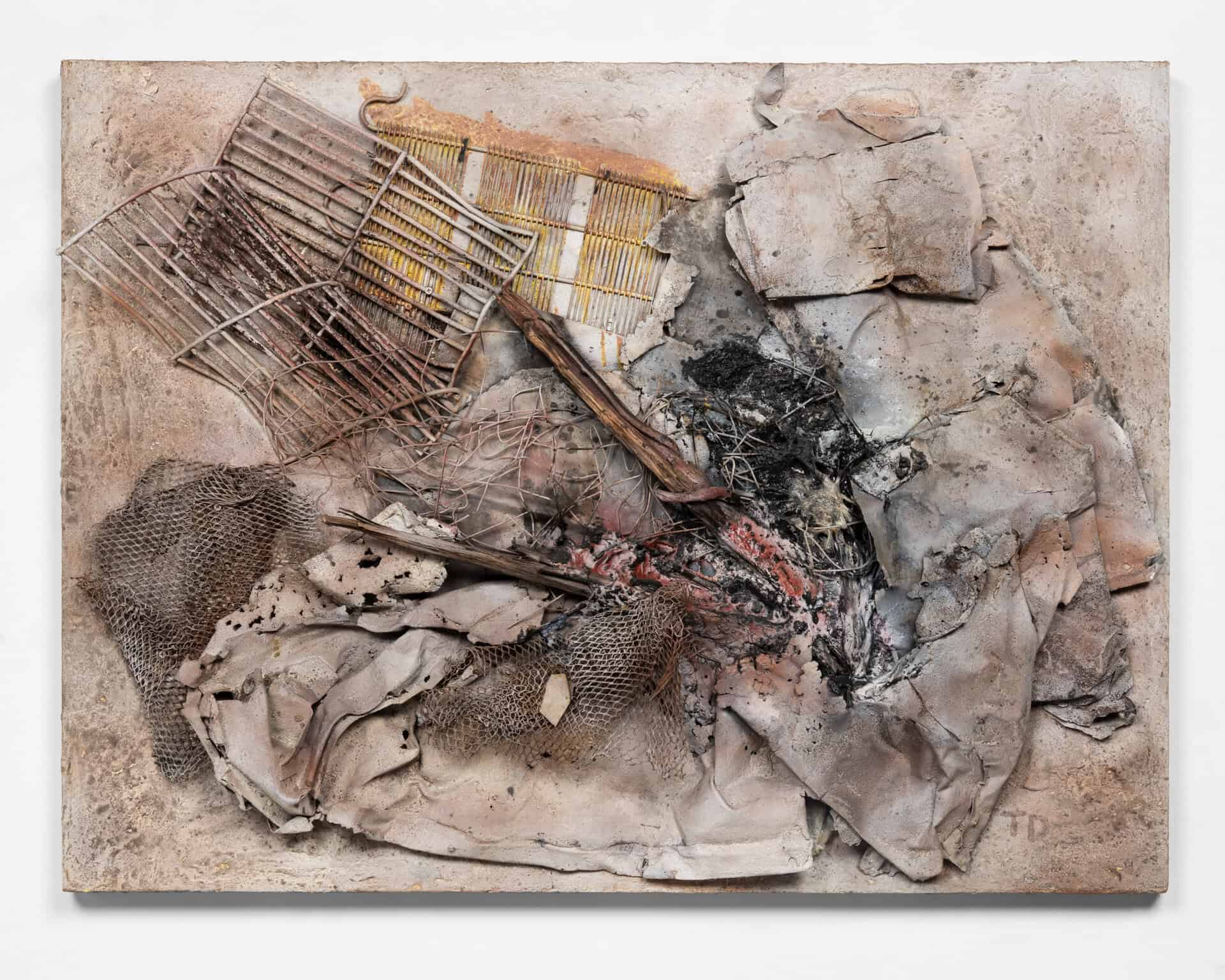

Conditioned by life experiences and rich senses of place and time, these artists’ highly personal artworks also speak eloquently for, and to, their communities of origin. For much of his adult life, Thornton Dial (1928–2016) worked as a welder at the Pullman-Standard boxcar factory in Bessemer, Alabama. Dial lived through the gradual demise of heavy industry and the region’s accompanying economic decline. His 2013 painting Feeding the Cupola—a cupola is a type of blast furnace for melting down iron in a foundry—uses that furnace as a metaphor for metamorphosis, the mysterious mixing of inputs such as memory and observation that, inside the human mind, generates creativity, originality, and radical beauty. Composed like a still life, Feeding the Cupola features an arrangement of scrap metal instead of a conventional bowl of flowers and fruit. This three-dimensional “painting” transforms Dial’s postindustrial world into an image equally gritty and lyrical.

Dial’s art, much like his life, defies easy categorization. Terms such as “folk art” or “outsider art” capture little of Dial’s work’s self-aware dynamism, its engagement with issues central to his community and culture, or the full panorama of his artistic references and sources. Sometimes creativity and human consciousness intertwine so closely that descriptors such as “artist” and “art” apply best.

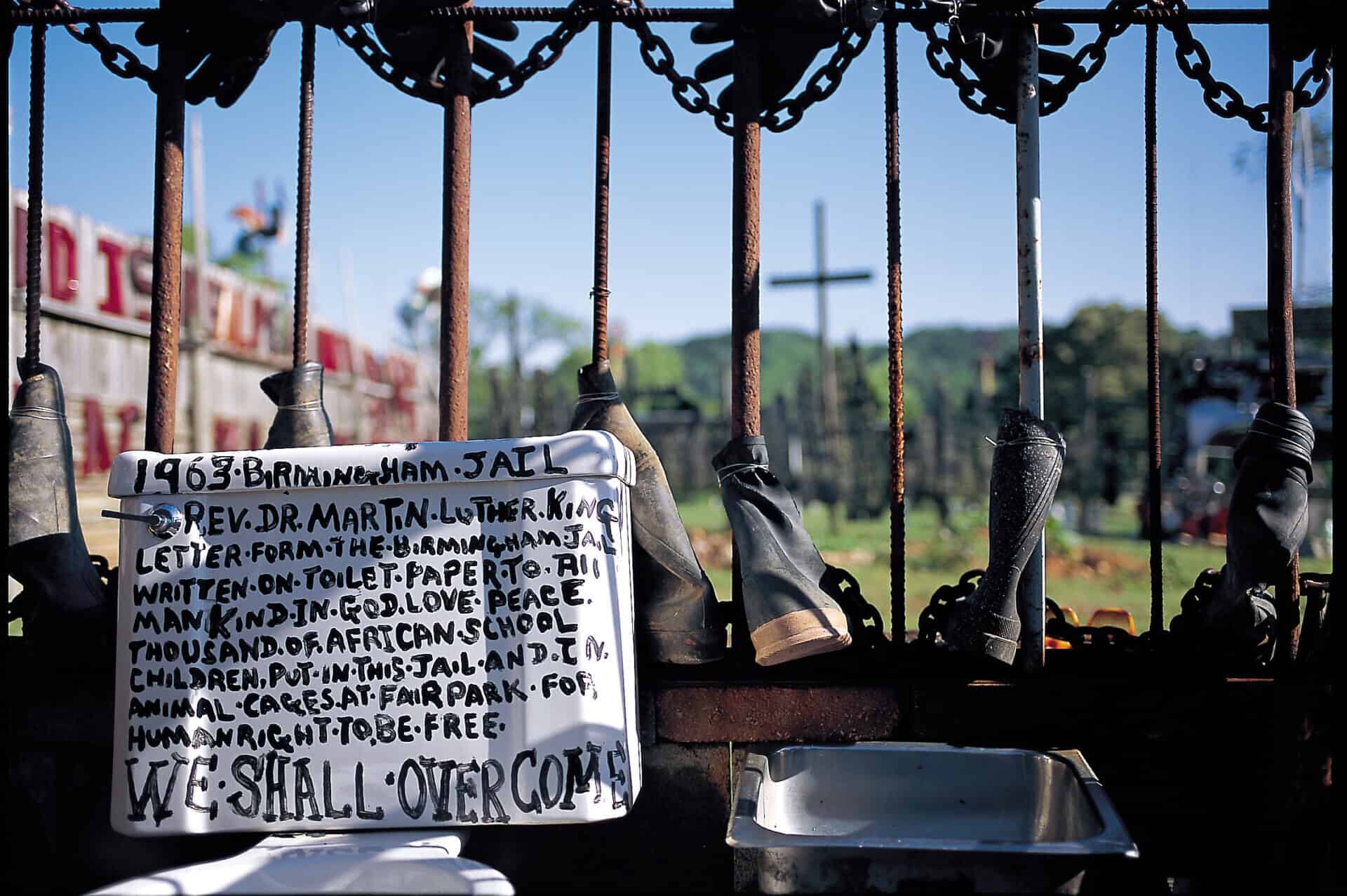

Lonnie Holley (b. 1950) made his first artworks—carved sandstone grave markers—as devotional tributes to two young relatives killed in a house fire. He was soon creating around the clock, and during visits to his local museum in Birmingham, Alabama, became enamored with Ancient Egyptian art, particularly its profile human faces and its use in honoring the dead. Relentlessly experimental, Holley has gone on to work in media ranging from sandstone carving, oil and acrylic painting, metal-wire mobiles and stabiles, drawing, found-object assemblage, cast-metal sculpture, and even computer-assisted images—on a scale stretching from the miniature to the monumental.

The original display contexts for Holley’s work (1980s and 1990s) were not official, art-designated spaces, but his own home and yard, which ultimately contained hundreds of works addressing historical, philosophical, and psychological topics. While Holley has discovered influences within fine-art traditions, his “yard show” (which was destroyed in the late 1990s) also drew extensively from aesthetic resources within his Southern Black culture. The category of yard art itself is a generations-old form of expression and presentation, seen throughout the American South and the African diaspora, that has afforded many Black artists an indigenous tradition resembling, yet ultimately distinct from, modern-art forms of assemblage and installation art.

The art makers in this genre share four significant characteristics. First, their work is serious in its goals, qualitatively compelling, and merits preservation and study. It deserves a place of its own in the story of world art. Second, their art is genuinely connected to the social transformations and political changes that have occurred over the course of their lifetimes. Third, the art came to exist despite steep odds and continual struggle, from members of one of the nation’s most encumbered minority groups, located in a region—the American South—not regularly associated with the visual arts. And fourth, they arrived at their mature artistic styles before they began to receive consequential attention from systems of consumption and institutions in the so-called mainstream art world. Indeed, this group of artists and their work reinforce the ongoing need to seek new ways of thinking about—and describing—not only the creative process, but also the social and intellectual structures that underlie simplified definitions and implicit hierarchies of accomplishment.