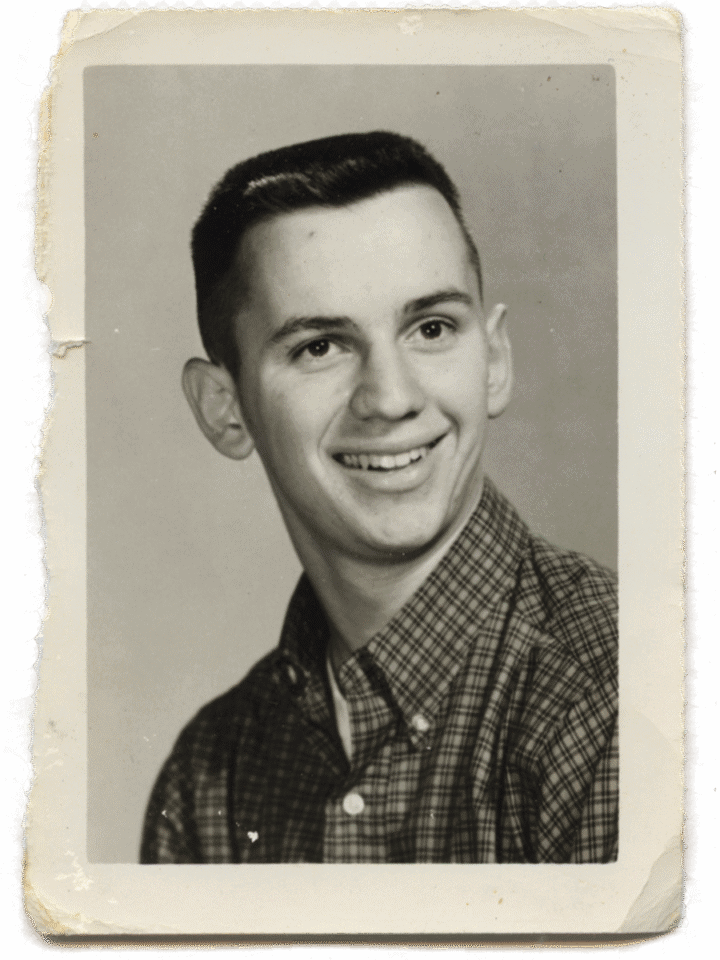

William S. Arnett

A native of Columbus, Georgia, William S. Arnett (1939–2020) was raised in the American South during the period of legalized segregation. As a child, he was already a collector (comic books, baseball cards, butterflies, marbles, autographs) and list creator, two encyclopedic tendencies that would later inform his approach to art and the civilizations that make it. His other great passions were music and sports. Both were severely regulated in the Jim Crow South of the 1950s: his local record stores did not sell the rock ‘n’ roll sung by now iconic Black musicians, and he was not allowed to play baseball with, or against, Black athletes. By the time he was a teenager, he had developed a lifelong belief that perceptions and understanding of culture—and with it, human potential in general—were unnecessarily constrained, even deformed, by the often tragic facts of sociopolitical structures.

After graduating from the University of Georgia, he left for London in the early 1960s, working as the European representative for an American company. His work required him to travel throughout the region, and he began to use his free time to visit museums and important religious and cultural sites. He soon became devoted to visual art and decided he wanted to spend his life in the arts. He left his job and began to travel more extensively outside of Western Europe, learning about and collecting art from the great ancient civilizations of the Mediterranean—Greek, Roman, Egyptian, and the still-older cultures of the Middle East.

By the mid-1960s, Arnett had also become interested in the civilizations of Asia, especially India, China, the countries of southeast Asia, and Japan. As his experience with art broadened—he ultimately traveled to more than sixty countries, often with his business partner and brother, Robert—he developed an inclusive sense of aesthetics and taste. He came to believe that human beings across time had created art of the highest sophistication in response to their widely varying histories, traditions, and imperatives. He was particularly interested in both the diversity and similarities of artmaking worldwide. He developed a theory that the arts played a crucial role in the development and survival of human culture, and were not merely a by-product of it. As he put it in the essay “Beyond Borobudur” (published in volume one of Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South), “Art, with its ability to unify and transform a population, could be as much a cause as an effect of a great civilization.”

Bill Arnett traveled to more than sixty countries to collect art and educate himself about human creativity and its many contexts. In the 1980s, he turned to his home region, the American South, and devoted the next three decades to championing its Black art and artists.

His interest in non-Western art led him, in the 1970s, to a nearly fanatical interest in aesthetics he believed had been wrongly derided as “primitive,” namely, the art of sub-Saharan Africa, Oceania, and the pre-Columbian Americas. He settled in Atlanta with his wife (and high-school sweetheart), Judy, and their four sons. He took on a more public role as a collector, regularly lecturing, lending art to museums, and organizing exhibitions of his own collections, all with the goal of educating audiences in the southern United States about the splendid diversity of the world’s art.

When a health condition limited his ability to travel in the mid-1980s, Arnett began to examine more closely the art forms of his native region. He had always maintained an interest in Black American art. Primarily through personal recommendations, he began to learn of Black artists from throughout the southern states. These individuals shared themes, working methods, and media—and had limited artistic and formal education, as well as little to no knowledge of each other. (Through Arnett’s efforts, many of the artists subsequently developed networks of friendships.) At first, Arnett was interested in correlations with African art. However, his understanding soon expanded. He considered the Black Southern artists to be constitutive of a largely unheralded art movement that had blossomed in the aftermath of the civil rights movement, amid social change and an emergent cultural consciousness the movement had engendered.

Arnett canceled plans he had made to retire to Europe. Inspired by these artists, he embarked on an altogether new collecting journey whose encyclopedic aim was to document the scope of the artists’ work and preserve it for posterity. He concluded that racial prejudice in the region had long existed in ignorance of an important expressive tradition within its Black culture. Moreover, he saw analogies to the ways cultural biases in an earlier era had blinded many to Black accomplishments and innovation in music and sports.

Arnett spent the rest of his life supporting and promoting this field of Black visual art. Working with living artists with complex needs, Arnett realized it would be necessary to assume responsibilities far beyond those of collector or dealer: as patron, archivist, documentary photographer, writer, publisher, and ultimately, philanthropist.

With Jane Fonda, in 2001 he founded a publishing company, Tinwood Books, to produce books and catalogs about this genre, most notably Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South (two volumes); the monograph Thornton Dial in the 21st Century; and a series of scholarly publications, including The Quilts of Gee’s Bend, on the now renowned patchwork quilts of Gee’s Bend, Alabama.

As early as 1988 he had decided that his Black art collection should, ideally, be turned into a nonprofit undertaking. Arnett’s greatest wish was for the art to survive the cultural headwinds and the capriciousness (and limitations) of taste that had long beleaguered the progress of art produced by marginalized groups. As he put it in a New Yorker profile from 2013, “Metaphorically speaking, I am betting on art.” Despite financial setbacks in the 1990s and early 2000s that delayed that vision, in the 2010s Arnett started the Souls Grown Deep Foundation and endowed it with more than 1,200 works by self-taught African American artists, with a goal of placing the art in the permanent collections of leading museums. Today, thanks to Arnett’s direct gifts and the activities of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Black American artworks originally from Arnett’s collection may be found in the permanent collections of dozens of leading museums. The Los Angeles Times has compared Arnett to John Lomax, the pioneering chronicler of American folk music, while the New York Times has likened his philanthropic vision to that of Samuel Kress and the Kress Foundation.

In 2020, the remainder of Arnett’s collection was bequeathed to establish the Tinwood Foundation, dedicated to expanding the body of knowledge related to Black art, artists and culture in the South.